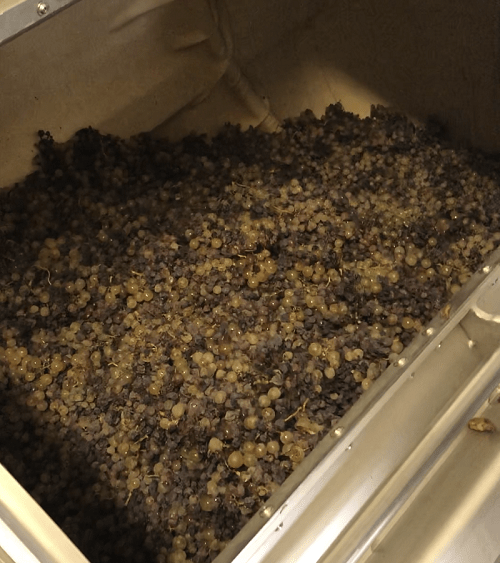

There’s something immediately refreshing about that first glimpse of harvested white wine grapes. For winemakers, white wine offers immediate satisfaction. These grapes often come onto the crush pad earlier than their black, burgundy, and red counterparts. Glistening with vitality, the production of white wine relies largely on the fruit itself. The clusters need to be ripe, healthy and handled gently yet quickly.

The main aim is to prevent oxidation along the entire process, from grape to must and then wine. While the process follows much of the same road map as red winemaking, the decisions, speed, and specifics change a bit. The impact of production decisions are profound here and treatments like skin contact, malolactic fermentation, and maturation vessels play a key role in the end style of white wines. Indeed, some wines are so impacted by their production methods that their very character becomes process-driven (looking at you creamy, buttery Chardonnay).

Winemakers start their process well before fermentation in the vineyard, where the ultimate ripeness of grapes determines the body, acidity, and character of a wine. Beyond that, much like red winemaking, the options boil down to:

- Before fermentation processing

- Fermentation

- Pressing

- Malolactic Fermentation

- Maturation

RELATED: How Red Wine is Made: The Red Wine Production Process

Clean Press

White wine grapes enter their enological path shortly after harvest and delivery to the winemaking site. The grapes are generally destemmed via a mechanical device that operates like a cylindrical coin counter which rotates on its side; holes are big enough for grapes to fall through for collection while the stems remain inside to be collected separately.

Because clean, fresh, healthy grapes are so crucial to white winemaking, pressing generally occurs very quickly after destemming. Whole bunch pressing (where grape bunches are left intact to be crushed) does occur in white wine making and is often preferred for a more delicate style of wine.

*Whole bunch pressing is often the preferred method for making white wines destined to become sparkling wines, but that’s a different article altogether.

Stems or no, grapes destined for white wine make their way to be pressed. This happens quickly to keep everything fresh and avoid oxidation. And like everything else in wine, while the tools to accomplish the task of pressing have evolved over time, the goal is the same: apply pressure and separate solid from liquid.

For those bunches who underwent destemming (and thus a form of crushing), a fair amount of free running juice is already in place. Free-run juice is widely recognized as the freshest juice. As such, it’s drained and set aside.

Then the pressure starts. Horizontal bladder presses offer a great amount of control over how much pressure. This bit of equipment looks like a horizontal tube with a rubber balloon in the middle. The grapes are loaded into it, the balloon (bladder) inflates and presses the grapes against the wall of the tube. Over time, the pressure increases, and with each increase the wine is separated and set aside. As the pressure goes up, the amount of grape skin compounds in the juice goes up right with it.

RELATED: Healthy White Wine and Rose Food Pairing Ideas With Recipes

Contact or Separation

Now, some white wines benefit from skin contact prior to fermentation…some don’t. More aromatic grapes (Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Muscat) and certain styles of wines (orange wines and Rhone white blends) derive a powerhouse of character from skin contact. The goal of enhancing a wine’s aromatic profile goes hand in hand with producing bigger-bodied wine.

Skin contact can last from a few hours to a day or more, depending on the end goal. Winemakers often keep the temperatures quite cool (again, avoiding oxidation) and add enzymes to speed up the process of those skins giving up their flavors to the must. The whole process is very carefully monitored so that the tasty compounds aren’t joined by the bitter compounds with which they coexist.

Getting Clarity

Now we have our white must and it’s time to make wine. One of the unsung heroes of white (and rosé) winemaking is clarification. The clarification techniques and processes all seek to remove the clouds of particles caught in the must and thus ensure a cleaner, brighter, less bitter future wine.

How, when, and how much clarification takes place depends on a few things:

- State of the fruit when it got to the winery

- Whether we destemmed the grapes or not

- The end goal for the wine’s style

The simplest and one of the more effective methods is to let the must rest at a cold temperature and wait for the clouds of sediment to fall. Then simply pump the now clear wine off the sediment. Called cold settling (for all the poetry in wine, none of it lives in the cellar) and is the gold standard of clarification methods.

Kicking Off the Party

Clarified and settled, the pre-wine must needs a fermentation vessel to carry it through its boozy journey. Stainless steels tanks, wood barriques (usually oak, though not always), and cement tanks are all available to winemakers.

Temperature control is key in white winemaking. So let’s just stop for a momentary look closer. We all remember this…right?

C6H12O6 → 2 C2H5OH + 2 CO2

This is the universal truth of fermentation, the chemical notation for the magic yeast works in wine. Upon consuming the sugar in the must, yeast produces alcohol (yay!), carbon dioxide, and heat. That heat? It builds up. Winemakers generally try to keep white winemaking fairly cool through fermentation. Too hot, and the wine losses its aromatics of fruit and flowers. Too cool and it can taste a bit…banana-ish.

Stainless steel fermentation vessels offer the most built-in temperature control, and many of them can be fully computer-controlled to report on the must’s temperature and allow for quick adjustments. Wood vessels tend to retain heat more readily, which if unregulated can insulate and warm a fermenting white wine. The type of wood, the shape of the vessel, and overall size can play into its suitability along with average temperatures in the winemaking region and facility.

Cement tanks come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. The interior of cement tanks is generally lined with an inert, easy-to-clean material like glass or epoxy resin. The bigger the tank, the more thermal mass and stability it has, and, unlike barrels, most cement tanks are able to house inserts which cool or warm wine must and control the temperature.

With the clarified must in the fermentation vessel, winemakers choose their yeast, and fermentation gets started. Yeast comes in two forms: free-range and cultivated. Cultivated yeasts are reliable and predictable, generally the preferred choice for winemakers who like to rest easy at night. Free-range, native yeasts offer less predictability but more character to a wine. Eventually, a dominant strain will win out, and that wine win tends to be a fairly reliable one, but there is a risk of unpredictability or a stuck fermentation.

Keeping Cool

Once fermentation gets rolling, there are two things winemaker’s control: the temperature of fermentation and the rate of fermentation. And yes, the two things are closely related. Just as a rule of thumb – cool and slow, hot and fast.

White wines can be fermented from temperatures as low as 52°F (11°C) and up to 68°F (20°C). The preservation of fruit aromas increases with lower temperatures. Fruit aromas are the result of compounds called volatile esters. These compounds, being volatile, can break down quickly or escape the wine if the must isn’t carefully handled.

Should a wine perk up above that 68°F (20°C) range, the yeast perks up and their activity perks up, forcing fruity flavors in a sharp decline. The opposite way, dipping below the 52°F (11°C) mark leaves the wine at risk of forming unattractive intense esters which smell of banana.

Style and Character

At the end of white wine fermentation, the temperature is dropped to a respectably chilly level, and the dead yeasts other coincidental material settles to the bottom of the tank. Here we reach a crossroads.

Lees contact and malolactic fermentation offer fullness, character, and complexity to many white wines. The greatest champion for both of these techniques is Chardonnay. Lees contact and lees stirring adds bready, brioche flavors. Malolactic fermentation adds notes of creaminess and a fleshier mouthfeel.

To be clear, malolactic fermentation (ML, MLF, Malo) is not an alcoholic fermentation. It’s just Lactic Acid Bacteria transforming malic acid (like the acidity of a granny smith apple) into lactic acid (like that of butter of cheese). It softens and smooths the bright feel into something more velveteen.

A white wine can, and many do, make it to the bottle without either treatment. The character of the grape is more than enough to impart ample flavor to the resulting glass. But, for more neutral or cool climate wines where the end style warrants a more robust framework, lees contact and malolactic fermentation offer their services.

Fresher styles of wine, those designed to be enjoyed young, may never see the inside of an oak barrel. However, there is a world of dry white wines that can achieve greatness through aging. White Burgundy, for example, can be aged for long periods in barrel on its lees. The character of the resulting wine is immense, developed through complex interactions with the barrel, air, wine, and lees.

Pour in the Light

The sheer variety of white wines, from grapes and process to maturation and release, leaves many heads spinning. At each step of the process, a critical decision which will determine what you have in your class is made. Bright, crisp, beguiling Riesling from Germany’s Mosel offers one glimpse. Sultry, silken, comforting Chardonnay from France’s Burgundy offers another.

Each region and every grape warrants a frame to accompany the picture it paints of the vintage, the region, and the winemaker. But the full picture of thoughtfully and masterfully created white wine doesn’t exist until you pour that first glass!

Frequently Asked Questions about How White Wine is Made

Learn More About Wine & Winemaking from Maisie

How Red Wine is Made Step-by-Step

How Do You Know When Grapes are Ready For Harvest?

Smoke Taint – What It Is & How It Affects Wine Grapes

You are reading “How White Wine is Made, Step-by-Step” Back To Top

making white wine, white wine production process, how do you make white wine: educational wine articles

If you enjoyed this guide, consider joining the Facebook Group to interact with other Winetravelers and for travel inspiration around the world, and be sure to follow along with us on Twitter and Instagram.

[…] into a press and the pressure is increased over time to separate the grape skins from the juice [7]. Some winemakers use yeast nutrients to bolster the fermentation, which is a mixture of white […]